A HISTÓRIA DA GALERIA DA ACADEMIA

O Galeria da Academia está localizado no centro histórico de Florença, na parte norte de Via Ricasoli, na confluência com Praça de São Marcos.

No seu interior, abriga o mais rico acervo de Michelangeloobras de 's, incluindo sete no total, entre as quais a famosa Davi destaca-se, e a mais extensa coleção de pinturas medievais em painel com fundo dourado do mundo.

Anualmente, é visitado por mais de um milhão e duzentos mil pessoas. Junto com o Academia de Belas Artes, ocupa um vasto complexo que se estende desde Via Battisti para Via Degli Alfani, de Praça da Santíssima Anunciação para Via Ricasoli.

O PRIMEIRO ASSENTO FORA DOS MUROS DA CIDADE: O HOSPITAL DE SAN MATTEO

Na era medieval, por volta do início do 1300s, nesta área conhecida como Cafaggio, que ficava fora dos muros da cidade até ser incorporada à expansão do segundo círculo comunal de 1280, também conhecido como ArnolfoNo círculo de 's, ficava o antigo mosteiro do Irmãs de San Niccolò em Cafaggio.

Ocupava a esquina entre Via dei Ciliegi (agora Via Alfani) e Via del Cococomero (agora Via Ricasoli).

Logo, em 1391, do outro lado da Via del Cococomero, na esquina da atual Praça de São Marcos, um hospital chamado San Matteo di Cafaggio foi construído para homens e mulheres. Foi encomendado pelo banqueiro Guglielmo (Lemmo) de Vinci de Graziano Balducci, que queria doar um hospital para a comunidade.

A construção do edifício foi confiada a 1385 para Rômulo di Bandino e Sandro del Vinta, “mestres da pedra e da madeira”, a quem pediu que erguesse uma loggia de canto na praça, seguindo o exemplo do Hospital Bonifácio em Via San Gallo. Em 1388, depois de vários acontecimentos, o banqueiro Lemmo confiou aos mesmos mestres a renovação do mosteiro das Irmãs de São Nicolau, instruindo-os a reutilizar as estruturas existentes do antigo mosteiro.

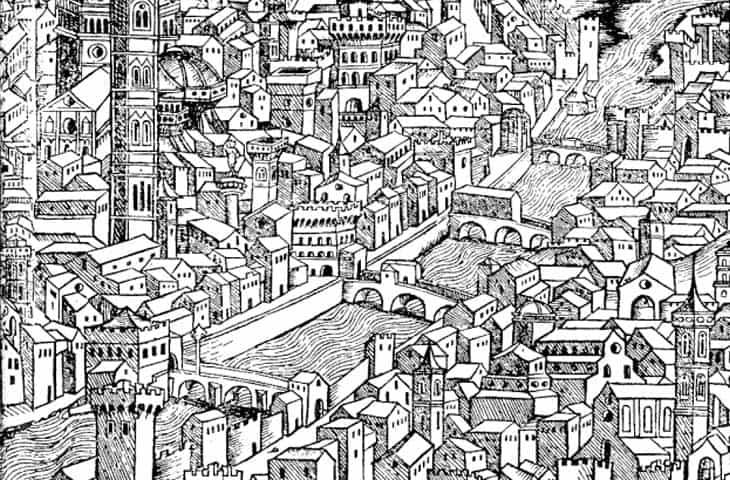

Em 1410, o Hospital San Matteo foi praticamente posto em serviço. Este traçado urbano, com a sua finalidade correspondente, permaneceu praticamente inalterado até Grão-Duque Leopoldo I da Lorena chegou. O mapa em perspectiva de Florença em 1584 pelo cartógrafo florentino Stefano Bonsignori (Nova Pulcherrimae Civitatis Topografia florentinaa) mostra com precisão o traçado urbano e os edifícios que foram erguidos na área de Cafaggio naquela época.

TRANSFORMAÇÕES DESEJADAS PELO GRÃO-DUQUE LEOPOLDO I DA TOSCANA

Com o advento de Grão-Duque Leopoldo I de Lorena, um soberano esclarecido do Grão-Ducado da Toscana e um grande reformador da século XVIII, mudanças significativas começaram nesta parte da cidade.

Desejava-se estabelecer uma cidadela das artes para promover o desenvolvimento cultural do Estado grão-ducal e o crescimento económico com o florescimento da Manufaturas artísticas toscanas.

Em 1784, o grão-duque emitiu um decreto conhecido como “motuproprio”, estipulando que todas as escolas de desenho existentes em Florença, incluindo a antiga Academia das Artes do Design fundada em 1563 por Cosimo de' Medici e frequentado pelos maiores artistas da época como Vasari, Bronzeado, Ammannati, Sansovino, Giambologna, e Celini, seriam unificadas em uma única Academia que adquiriria o nome clássico mais moderno de A Academia de Belas Artes, “todas as escolas pertencentes ao Design, e a Academia que as presidirá.”

Além disso, decidiu-se criar uma galeria ao lado para abrigar as pinturas antigas que estavam sendo adquiridas. Por meio dessas obras, os jovens estudantes enriqueceriam sua educação artística estudando, observando e reproduzindo as obras originais ou imitadas de mestres italianos do Renascimento e além.

Estudos na Academia eram gratuitas e abertas a todos os que se candidatassem, e as disciplinas de ensino foram estabelecidas: pintura, escultura, composição de cores, desenho de figuras nuas, gravura em cobre, arquitetura e “garrotes” (posteriormente modificado para design ornamental).

A nova organização do Academia em 1783 foi estabelecido dentro do antigo Hospital do Convento de San Matteo, na esquina da atual Praça de São Marcos, cuja reconversão funcional e distributiva foi confiada ao arquitecto Gaspare Mattia Paoletti, professor de arquitetura na Academia, e seus colaboradores Bernardo Fallani e Giuseppe Paoletti.

As transformações planeadas e dirigidas por Paulo e seus colaboradores envolveram principalmente o preenchimento do 1Século IV loggia em Via del Cococomero, agora Via Ricasoli (a restauração da loggia do século XIV, tal como se apresenta hoje, teria de esperar até 1931), a construção de um edifício adicional acima dele para acomodar as escolas de desenho de figuras humanas, gravura em cobre, pintura e design ornamental, a adaptação dos espaços originais destinados aos hospitais para homens e mulheres em galerias de exposição e as transformações funcionais necessárias para incluir serviços e acomodações para os diretores da Academia, bem como a disponibilização de espaços para estabelecer estúdios de artistas espalhados pela cidade.

Nas duas galerias concluídas já em 1784, a extensa produção artística da escola logo foi exposta.

Grão-Duque Leopoldo, então voltei sua atenção para o Convento adjacente do Freiras de San Niccolò, o antigo mosteiro de San Niccolò di Cafaggio, localizado no início de Via del Cococomero, na esquina da Via del Ciliegio (agora Via Alfani), adquirindo todo o complexo em 7 de maio de 1787, para a soma de 5,315 lire. Ele confiou ao arquiteto Bernardo Fallani a transformação e adaptação.

Em 1796, o Opinião delle Pietre Dure (Oficina de Pedras Semipreciosas) foi estabelecido dentro do antigo convento das Freiras, mudando-se de sua localização original no Uffizi, e mais tarde, em 1857, foi fundada também a escola de música, hoje Conservatório Luigi Cherubini, após um projeto de reforma da parte do edifício na esquina das duas ruas, realizado pelo arquiteto Francisco Mazzei.

O século XIX representações planimétricas mostram os dois complexos de edifícios contíguos e unidos sob o Instituto do Academia Real de Belas Artes. Desta forma, o Grão-DuqueA ideia de transformar uma área estratégica da cidade em uma grande oficina de cultura e arte foi concretizada, a ponto de, no final do século 18º século, a operação poderia ser considerada concluída.

No Galeria desejado pelo Grão-Duque para apoiar os estudos acadêmicos, foram colocados moldes e moldes de gesso na antiga enfermaria masculina do Hospital de São Mateus.

Entre estes estavam os Rapto das Sabinas de Giambologna (uma cópia em gesso do grupo de mármore exposto na Loggia dei Lanzi) e a Alegoria de Florença dominando Pisa (agora exibida em Palácio Velho), assim como vários desenhos e modelos. Na ala feminina, as pinturas foram exibidas.

Com a supressão das instituições religiosas e dos conventos em todo o território florentino, primeiro pela Grão-Duque de Lorena no final 18º século e depois por Napoleão Bonaparte no início 19º século, novas obras, principalmente de temática religiosa, executadas pelos principais mestres que trabalharam em Florençae seus arredores, da segunda metade do século XIII até o final do século XVI, vieram enriquecer o acervo de pinturas.

Estes incluem a Maestà de Cimabue e Giotto, a Sant'Anna Metterza de Masaccio e Masolino, a Adoração dos Magos de Gentile da Fabriano, a Batismo de Cristo por Leonardo da Vinci, e a Ceia em Emaús por Pontormo. Em particular, a coleção de pinturas em painel com fundo dourado é única no mundo por seus numerosos exemplares.

A GALERIA DA UNIDADE DA ITÁLIA

Após a Unificação da Itália, a Galeria foi enriquecida com muitas obras modernas, o que levou ao seu reconhecimento como a Ancestral e Galeria Moderna. Foi o primeiro museu de arte contemporânea no emergente Estado italiano.

Em 1872, após várias décadas de observação cuidadosa e diligente por três comissões de estudo criadas especificamente para avaliar o estado de preservação do mármore, ocorreu um evento histórico que moldaria a vida futura do Galeria.

Com base nos resultados alarmantes fornecidos pelos especialistas, a Município de Florença decidiu transferir Michelangelobloco de mármore de David da escadaria de Palácio Velho, onde a sua integridade física estava em risco devido à longa e contínua exposição ao meio externo, Via Ricasoli dentro do Galeria da Academia.

Para esta ocasião, foi especialmente construída uma plataforma retangular ligada a uma êxedra semicircular, localizada no final do salão de pinturas antigas (hoje o Corredor dos Prisioneiros), com uma claraboia no topo para iluminação natural da magnífica obra de arte.

Em 1882, ocorreu outro episódio agudo para o Galeria da Academia—a inauguração do Museu Michelangelo por ocasião do centenário do nascimento do grande mestre. Contou com a exposição de moldes de suas obras significativas, como a Túmulos dos Médici, Moisés, o Pietà do Vaticano, o Pietà Rondanini, o Cristo da Minerva, e o Prisioneiros, que circundava a estátua original recentemente colocada de Davi dentro da Galeria, dentro do De Fabris Tribune.

Ao mesmo tempo, a Galeria se separou do Instituto de Belas Artes. Tornou-se anexa às Galerias e Museus Reais, confirmando a nova direção da Academia, que se concentrava mais na promoção da arte contemporânea (de fato, durante esse mesmo período, Florença vivia um dos momentos mais fecundos da produção artística graças ao Movimento Macchiaioli) em vez de reproduzir disciplinas clássicas e passadas de acordo com o espírito predominante na época da criação da escola leopoldina.

Como resultado, a coleção de obras de arte se tornou objeto de preservação, documentação e um testamento de períodos históricos passados principalmente. Em linha com essa nova abordagem, uma entrada direta para a Galeria foi aberta na Via Ricasoli para visitantes.

NOVAS CHEGADAS EM 1900 E NO PERÍODO CONTEMPORÂNEO

Em 1909, o Galeria da Academia foi enriquecido pela chegada do Prisioneiros (também conhecidos como escravos desde o século XIX), quatro esculturas poderosas de nus masculinos de Michelangelo. Elas foram trazidas para dentro de casa, pois corriam risco de degradação devido à exposição prolongada e contínua ao ambiente externo. Essas quatro esculturas, parte de uma série de seis estátuas (os dois primeiros estão localizados no Museu do Louvre em Paris), são mais significativos do que o tamanho real, retratados em várias poses como prisioneiros, não totalmente libertados do material pelo artista e, portanto, inacabados, foram esculpidos por Michelangelo para Papa Júlio IIo túmulo em Roma.

Até então, eles enfeitavam o Gruta de Buontalenti no Jardins de Boboli, colocado ali pelo Grão-Duque Cosimo Eu, a quem foram doados por Leonardo Buonarroti, sobrinho do grande artista, após sua morte. Os recém-chegados foram colocados após o vestíbulo da entrada em Via Ricasoli na primeira Galeria, mais tarde denominada Galeria dos Prisioneiros.

Eles se juntaram ao famoso grupo de São Mateus, já presente no Academia, e foram acompanhados pelo Pietà de Palestrina (um grupo de mármore representando dramaticamente o Jesus morto, desmaiado sobre as pernas e apoiado pela Mãe), que veio da Capela de Palácio Barberini em Palestrina, perto de Roma, após sua aquisição pelo Estado italiano em 1939.

Com as novas chegadas, a Galeria de pinturas antigas adquiriu um valor orgânico na vida artística de Michelangelo Buonarroti. Tornou-se a coleção mais abundante do grande mestre preservada em um museu.

Durante este período, sob a direção de Cosimo Ridolfi, o Galeria da Academia sofreu uma nova transformação, afetando principalmente a coleção de pinturas. Junto com a reorganização das pinturas antigas com sua realocação em salas especificamente designadas, como as dos séculos XIV, XV e XVII, novos espaços de exposição foram criados na ala esquerda da Tribuna, agora conhecidos como Salas dos séculos XIII e XIV, Orcagna e seus seguidores, e Escola de Giotto, onde funciona por Botticelli e Perugino encontrou melhor colocação.

Guias de viagem de Florença Você pode gostar – 2025

Em volta do 1920s, como parte de um arranjo geral dos museus da cidade e dos acordos resultantes entre o Município de Florença e o Estado, todas as pinturas de temas modernos foram transferidas para a Galeria de Arte Moderna de Palácio Pitti. Outro grupo de obras de autores da escola florentina foi atribuído ao Galeria Uffizi.

Ao mesmo tempo, as obras de Beato Angelico foram direcionadas para a vizinha Museu de San Marco, o depositário das obras de Angelico.

Na década de 1930, o Colosso e Anticolosso quartos foram incorporados no andar térreo. Eles foram nomeados assim porque abrigavam o molde de gesso de uma estátua antiga, um dos Dioscuri de Monte Cavallo.

Eles foram designados para acomodar grandes retábulos do século XVI Período florentino. Após essas transferências, a Galeria perdeu qualquer conotação de galeria moderna e tornou-se, após esse episódio, a Galeria da Academia.

Em volta do 1950s, sob a direção de Luisa Becherucci, a reorganização dos cômodos do térreo começou com os salões Colossos. No centro da entrada principal, o modelo do O estupro das mulheres sabinas em terra crua, obra do escultor flamengo Jean de Boulogne, conhecido como Giambologna, executado em torno de 1582, foi colocado.

Como vimos, sua versão em mármore ainda está localizada sob o Loggia dei Lanzi em Praça da Signoria. Numerosos exemplos de florentino pintura em painel e tela da 15º e XVI, incluindo obras de mestres renomados como Paulo Uccello, Botticelli, Perugino, Filippino Lippi, e Ghirlandaio, foram exibidos nas paredes. Os dois cômodos foram reorganizados novamente no 1980s, sendo a sala menor destinada à bilheteria e livraria e às obras de Pontormo, Bronzeado, e Alessandro Allori sendo transferido para a sala dedicada a Michelangeloobras de 's, substituindo as tapeçarias.