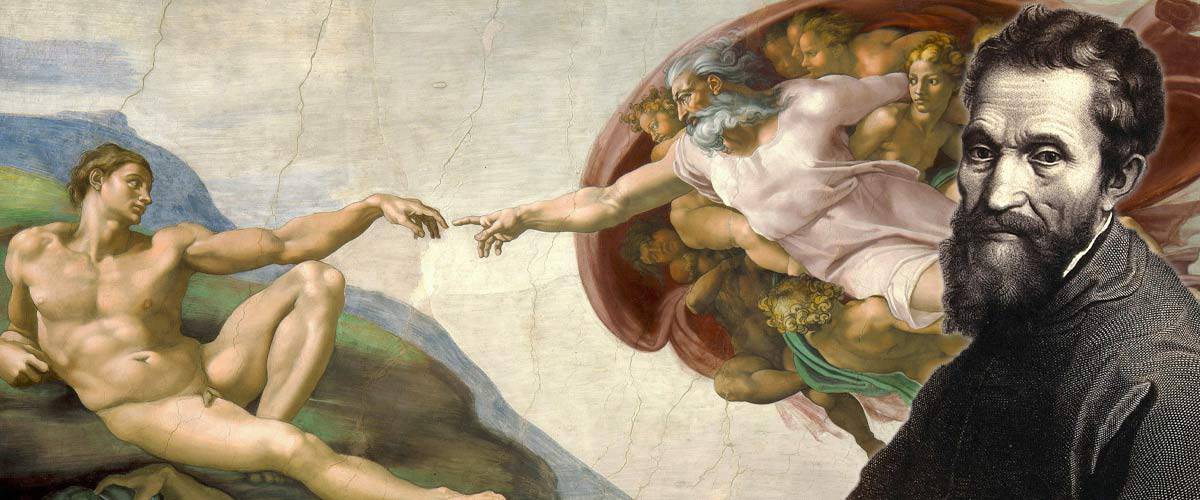

Michelangelo Buonarroti

Michelangelo Buonarroti was an unparalleled artist, sculptor, painter, architect, and poet; his genius was expressed in masterpieces that continue to fascinate and move audiences around the world.

From the monumental “David” to the sublime Sistine Chapel, from the architecture of St. Peter’s dome to the intense poetry of his sonnets, Michelangelo explored every art form with unsurpassed mastery, raising the boundaries of beauty and perfection to heights never reached before.

On this journey through the life of Michelangelo Buonarroti, we will immerse ourselves in the world of Michelangelo. We will discover a complex and tormented man, continually searching for perfection. This visionary genius captured the essence of the human soul. It transmitted it in his works with an unparalleled expressive force.

Caprese’s birthplace

On March 6, 1475, a child was born in the small town of Caprese. This child, named Michelangelo by Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni, was destined to change the art world forever.

His father, Ludovico di Leonardo Buonarroti Simoni, was a magistrate of the small town, a man of modest resources. His mother, Francesca di Neri del Miniato di Siena, was a woman of delicate health but immense character strength.

During her pregnancy, Francesca had an accident. It was a terrifying moment. Yet the child was born healthy; his parents named him Michelangelo, which means “like an angel.”

From an early age, Michelangelo showed signs of the genius he would become.

The Death of the Mother

In 1476, the Buonarrotis decided to return to Florence. Still, little Michelangelo was entrusted to the care of a wet nurse in the nearby city of Settignano, famous for the quarries of the beautiful Pietra Serena.

The nurse’s husband was a stonemason, a man who shaped marble into different shapes.

In an environment steeped in dust and art, it was here that Michelangelo had his first encounters with marble and master stonemasons.

Growing up in Settignano, his nurse’s family wasn’t just taking care of him—they were unknowingly introducing him to the world of sculpture. These early experiences would leave an indelible mark on him, laying the foundation for his future as one of history’s greatest sculptors.

However, just as Michelangelo began to connect with the world around him, tragedy struck.

At the age of just six, he lost his mother. Although he did not spend much time with her, their bond was deep, and her sudden death left an unfillable void in the child’s heart, a pain that would accompany him throughout his life.

This profound loss, combined with his childhood difficulties, undoubtedly influenced Michelangelo’s character. He grew up introverted and often tormented, marked by constant melancholy.

However, Michelangelo found in art the power to express his pain, anger, and frustration. Sculpture and painting became his way of communicating with the world, transforming his inner turmoil into masterpieces that continue to resonate today.

A young Michelangelo in Ghirlandaio’s workshop

Forced by necessity, Ludovico, Michelangelo’s father, entrusted him to the care of Domenico Ghirlandaio, one of the most renowned Florentine artists of the time. Thus, on June 28, 1487, at just thirteen years old, Michelangelo Buonarroti crossed the threshold of the master’s workshop.

In Ghirlandaio’s workshop, Michelangelo immersed himself completely in learning artistic techniques. He drew tirelessly, studied anatomy on the corpses of the Santa Maria Nuova Hospital, and dedicated himself passionately to sculpture and painting.

His innate talent soon emerged, arousing the admiration of Ghirlandaio and the other artists in the workshop.

Despite these successes, Michelangelo’s childhood was marked by a profound inadequacy. His once aristocratic family had fallen into disgrace, depriving him of the classical education reserved for the young people of the Florentine upper class.

Throughout his life, Michelangelo tried to hide this shortcoming, inventing stories about a “Divine calling” to art to justify his irregular education.

The obsession with redeeming the Buonarroti name and affirming his artistic genius became the driving force of his existence. Michelangelo was not satisfied with being a simple craftsman; he aspired to achieve immortality through his works.

The period spent in Ghirlandaio’s workshop represented the first step on this ambitious journey. Among the smells of paint and the noise of chisels, Michelangelo laid the foundations to become one of the greatest artists of all time.

Michelangelo in the De’Medici Garden

Michelangelo was soon noticed by Lorenzo de’ Medici, one of the most influential patrons of the time. Lorenzo, struck by the young artist’s talent, invited him to live and work in his palace, introducing him to the prestigious Garden of San Marco.

This garden was a place of natural beauty and a genuine artistic laboratory, where Michelangelo had access to the most refined sculptural techniques and the company of the best Florentine artists and intellectuals.

Soon, the young and talented Michelangelo came into conflict with Pietro Torrigiani, another ambitious sculptor who was a pupil of Bertoldo, the head and master of the Medici school founded by Lorenzo the Magnificent. However, in one of their most violent clashes, Michelangelo got the worst: Torrigiani hit him with a hard punch that ruined his face forever.

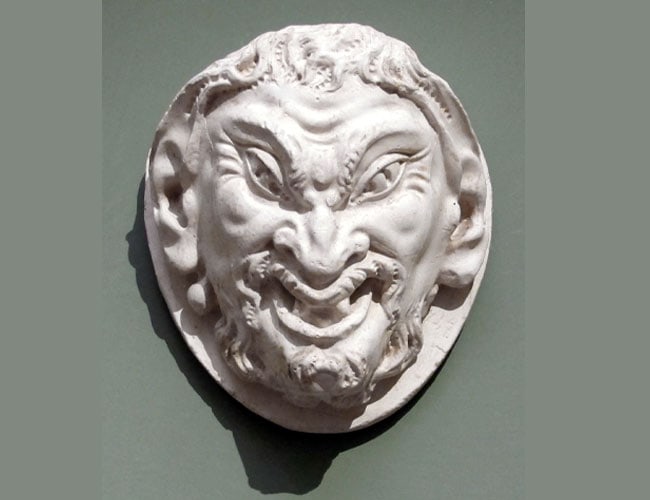

In the Garden of San Marco, Michelangelo sculpted his first masterpiece, the “Head of a Faun,” which already displayed an astonishing skill in handling marble.

But it was with the “Battle of the Centaurs,” a relief representing a mythological scene full of dynamism and tension, that Michelangelo fully expressed his creative potential.

Simultaneously, he worked on the “Madonna della Scala,” a relief that combined the grace of classical figures with a profoundly personal emotional intensity.

These works cemented his reputation as a young prodigy. They began a career that would change the art world forever.

You can already appreciate Michelangelo’s innovative technique, which pushes the chisel well beyond the surface of the marble. In contrast, other sculptors prefer to approach only with the rasp for fear of damaging the work.

Conversely, Michelangelo dares to go deeper, risking compromising the entire sculpture with a too-decisive blow. This audacity, this ability to push the limits, makes his technique unique and distinguishes him from other artists of his time.

Michelangelo Buonarroti Escape from Florence

Michelangelo remained at the Magnificent Court until 1492, Lorenzo de’ Medici’s death. Soon after, Florence went through a period of significant political instability, aggravated by the rise of Girolamo Savonarola, a Dominican friar who preached moral reform in the city and who, following the expulsion of the Medici, became a figure of growing influence.

Sensing the danger, the young Michelangelo decided to take refuge in Bologna, where he remained for the time necessary for the political turbulence in Florence to calm down. During his short stay in Bologna, he sculpted some works, including the “San Procolo” and “San Petronio,” demonstrating his extraordinary talent and ability to adapt to new artistic challenges.

Michelangelo Returns to Florence

In 1495, Michelangelo returned to a still unstable Florence, a city he no longer recognized as his, and felt lost. However, he did not let himself be discouraged and resumed sculpting, creating a “Sleeping Cupid” with such mastery that he managed to deceive Cardinal Giorgio Raffaele Riario, who purchased the work for 200 ducats, believing it to be an ancient Roman sculpture.

When the cardinal discovered the truth, he was so impressed by Michelangelo’s talent that he invited him to Rome, thus opening a new phase in the artist’s career.

Rome, a lively center of art and culture, offered him the opportunity to show his extraordinary talent. His first major commission came from the powerful Cardinal Riario, who, impressed by Michelangelo’s previous work, commissioned him to create a statue of Bacchus.

However, the work only partially satisfied the cardinal, who found it lower than his expectations.

Faced with the failure of this project, Michelangelo did not allow himself to be discouraged. He used this experience to refine his craft further, focusing on new artistic challenges.

The Rebirth of Michelangelo Buonarroti in Rome

Shortly after that, he was entrusted with creating the Pietà, a work that gained worldwide recognition, consolidating his status as an artistic genius and paving the way for future commissions of great prestige.

Michelangelo’s Pietà is one of the world’s most famous and admired sculptures, created between 1498 and 1499. It represents the Virgin Mary holding the lifeless body of Jesus Christ in her lap.

One of the most surprising features is the representation of Mary as a young woman, almost the same age as Jesus. This artistic choice underlines the human aspect of pain and the mother’s deep emotion in the face of her son’s death.

The figures are sculpted with ideal proportions, enhancing the beauty and perfection of the human body.

The faces of Mary and Jesus express deep and intense pain but, at the same time, an almost mystical serenity.

The work is made from a single block of white marble, crafted with a technical mastery that has aroused the admiration of generations of artists.

David: the most famous work in the world

After the triumph of the Pietà, Michelangelo Buonarroti returned to Florence, where his fame preceded him. In 1501, he was commissioned one of the works that would define his career: David.

This colossal marble statue, more than five meters high, quickly became the symbol of the Florentine Republic and its resistance against external threats.

David represented not only Michelangelo’s unparalleled technical skill but also his profound understanding of human anatomy and ability to breathe life and emotional tension into stone.

The work, completed in 1504, further cemented Michelangelo’s reputation as the greatest sculptor of his time, attracting the attention of influential patrons, including Pope Julius II, who would soon call him to Rome to undertake even more ambitious projects, like the frescoes in the Sistine Chapel.

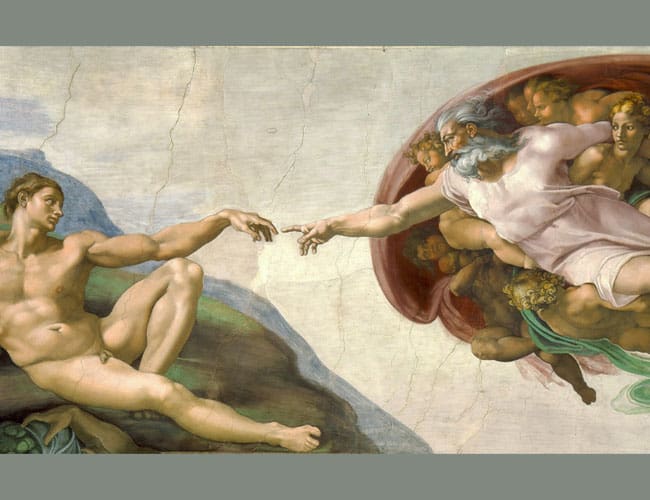

The Sistine Chapel

Having arrived in Rome at Pope Julius II’s invitation, Michelangelo faced the most imposing challenge of his career: the frescoes on the vault of the Sistine Chapel. This monumental project, begun in 1508 and completed in 1512, required the artist to overcome the limits of his experience, being primarily a sculptor.

Working in grueling conditions, often lying on scaffolding several meters in the air, Michelangelo created a masterpiece that would influence Western art for centuries. The Sistine Chapel vault featured biblical scenes of extraordinary complexity and beauty, including the famous “Creation of Adam.”

The work demonstrated Michelangelo’s versatility as an artist and revealed his profound theological knowledge and his ability to translate spiritual concepts into images of powerful visual impact. The scale and ambition of this work were unprecedented, with over 300 figures painted over a surface area of over 500 square meters.

This period also began a complex and often tumultuous relationship with the Church and its patrons, which would characterize much of his later career.

Overly ambitious projects: The Tomb of Julius II

After completing the Sistine Chapel frescoes, Michelangelo dedicated himself to ambitious projects, alternating papal commissions and works for private clients. One of the most significant projects of this period was the tomb of Pope Julius II, a feat that would haunt him for decades.

Initially conceived as a gigantic monument with over 40 statues, the tomb underwent numerous revisions and delays. This project, which Michelangelo called the “tragedy of the burial,” became a source of frustration and conflict with the heirs of Julius II. Despite the difficulties, the artist created some of his most famous works for this tomb, including the powerful “Moses.”

Furthermore, this monumental project left us an unexpected legacy: a series of unfinished statues, known as the “Prisoners” or “Slaves,” which we can admire today at the Galleria dell’Accademia in Florence.

Deliberately left unfinished, these sculptures offer a unique glimpse into Michelangelo’s creative process and are considered among his most exciting and mysterious works. The figures, which seem to emerge from the rough stone, embody the soul’s struggle to free itself from matter, becoming powerful symbols of Michelangelo’s artistic vision and his conception of sculpture as the liberation of form from the block of marble.

The Last Judgment

In 1534, Pope Paul III commissioned him to paint the “Last Judgment,” another monumental fresco for the altar wall of the Sistine Chapel. This work, completed in 1541, displayed even greater artistic maturity and emotional depth than his previous works. The “Last Judgment” attracted admiration and controversy for its bold and often naked depiction of biblical figures.

During this period, Michelangelo also became increasingly involved in architecture. In 1546, he was appointed chief architect of St. Peter’s Basilica, a role he would retain until his death. His design for the dome of St. Peter’s became one of his most enduring and influential architectural legacies.

The last few years

In the last years of his life, Michelangelo focused primarily on architecture and poetry, showing the breadth of his creative genius. His work on St. Peter’s Basilica continued to be the focus of his architectural endeavors. Still, he also devoted himself to other significant projects in Rome.

Among these, the design of the Piazza del Campidoglio and the transformation of the Baths of Diocletian into the Basilica of Santa Maria degli Angeli e dei Martiri stand out. These designs demonstrated his ability to fuse classical aesthetics with structural and spatial innovations, profoundly influencing the late Renaissance and Baroque architecture.

Parallel to his architectural work, Michelangelo dedicated himself to sculpture and poetry with increasing intensity.

His last sculptures, such as the “Pietà Rondanini,” which remained unfinished at his death, showed a stylistic evolution towards more abstract and spiritual forms, anticipating artistic trends that would develop centuries later.

His poetic production of this period, mainly sonnets and madrigals, revealed a profound introspection and reflection on mortality, love, and faith. Initially shared only with close friends, these verses would be published posthumously, revealing another aspect of his multifaceted genius.

Michelangelo’s Last Week

The last week of Michelangelo Buonarroti’s life was characterized by quiet contemplation. The great artist, now exhausted by age and a mysterious illness, spent his days reflecting on his extraordinary existence. His eyes, once burning with passion, were now clouded with melancholy, and his hands, creators of immortal works, trembled tiredly.

Despite his physical decline, Michelangelo’s mind remained sharp. He shared his most profound thoughts on art, beauty, and the transience of life with friends. His words, full of wisdom, revealed a serene acceptance of the imminent end.

Michelangelo explored the theme of death in his poetry, sometimes expressing the fear of divine judgment and other times finding comfort in faith. Now, faced with the inevitable, he showed the same courage that had distinguished him all his life.

On February 18, 1564, at 88, Michelangelo passed away. His last words, addressed to his friend Daniele da Volterra, were a whisper full of affection: “O Daniello, I am doomed; please, don’t abandon me.” At his bedside, in addition to Daniele, there was Tommaso de’ Cavalieri, his beloved confidant, and shortly afterward, his favorite nephew Lionardo Buonarroti arrived, urgently called from Rome.

Thus ended the life of a legend, a man who had devoted all his energy to creating beauty, leaving an artistic legacy that continues to inspire the world.

Michelangelo: Mind of the Master

Links you might find useful

Tickets & Tours

Accademia Gallery

Visitor Information

Opening Hours

Tickets and Tours

Accademia Online

Radio Accademia

Florence Attractions

Uffizi Gallery

Duomo Florence

Palazzo Pitti

More Florence Attractions